Barrier Delay Measures and The Double Edged Sword

While assisting a reporter after the Uvalde shooting, a question was posed that maybe warrants some discussion. During the interview, I described some examples of common physical security problems I encounter in schools including choice of classroom door locks among other issues.

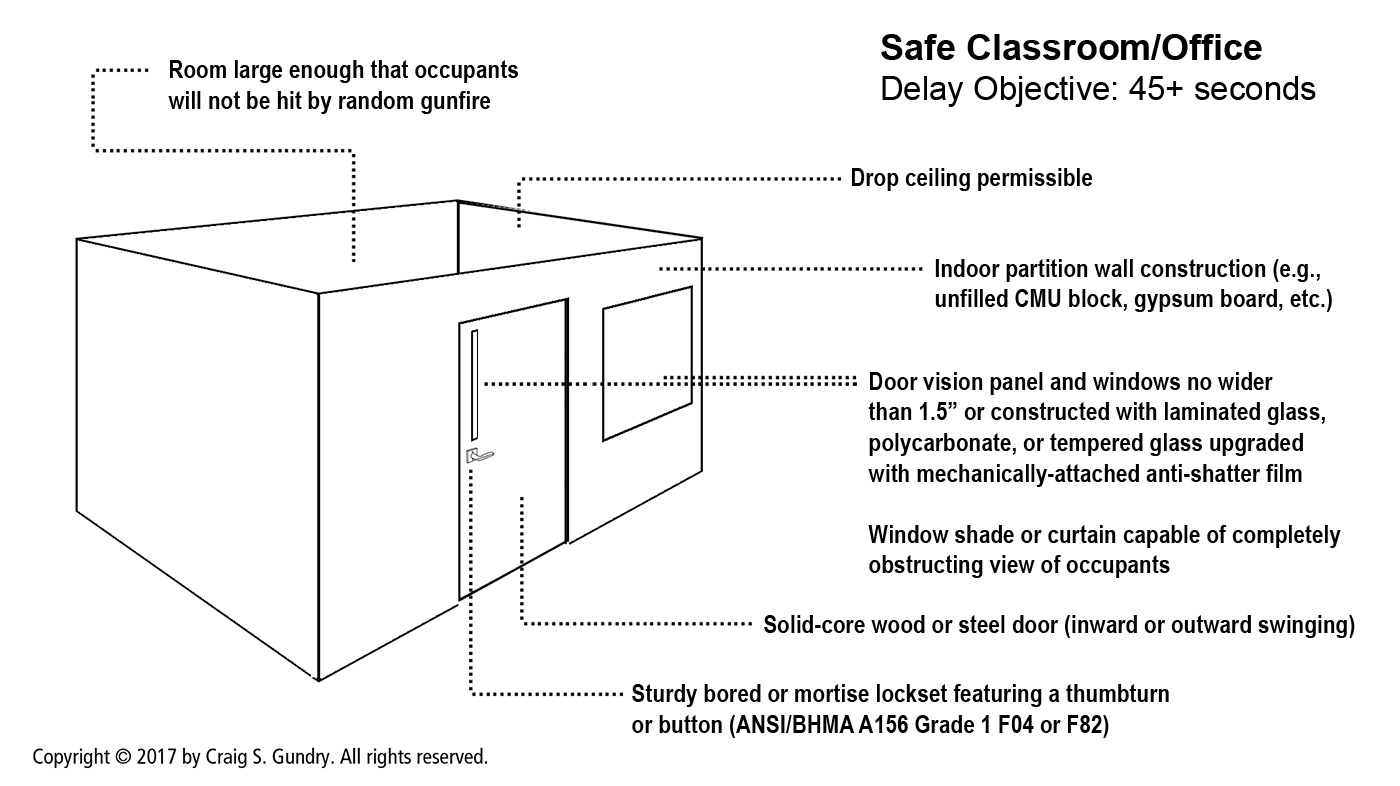

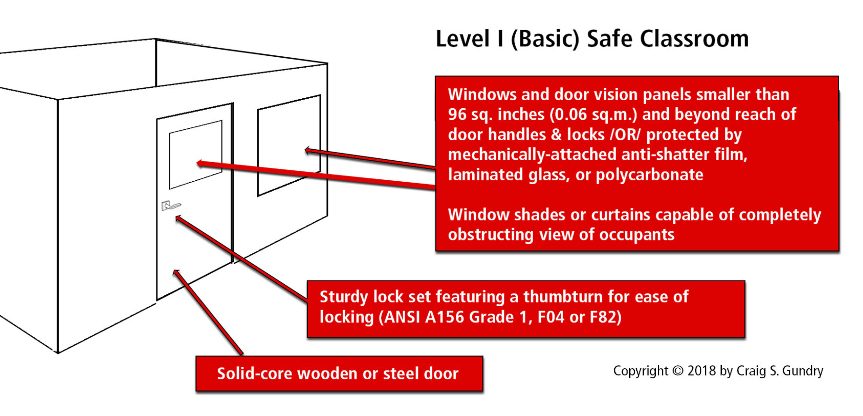

Those who have read my previous articles or attended my courses have heard me preach against the use of “classroom-function” locks (ANSI F05 and F84) in favor of “office-function” locks (ANSI F04 or F82). The concern about “classroom-function” door sets is that they require a teacher to lock the door using a key from the outer side of the door. This may not sound like a big deal to a casual observer, but this situation is a recipe for disaster when a teacher needs to locate a set of keys, open a door to the hallway without knowledge of the gunman’s location, and manipulate keys under the debilitating effects of the Sympathetic Nervous System. And if a teacher is absent at the time an attack occurs, students in the classroom have no way of securing the door.

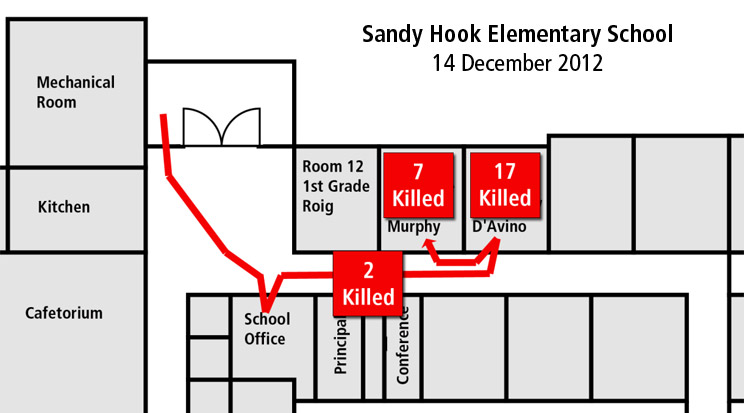

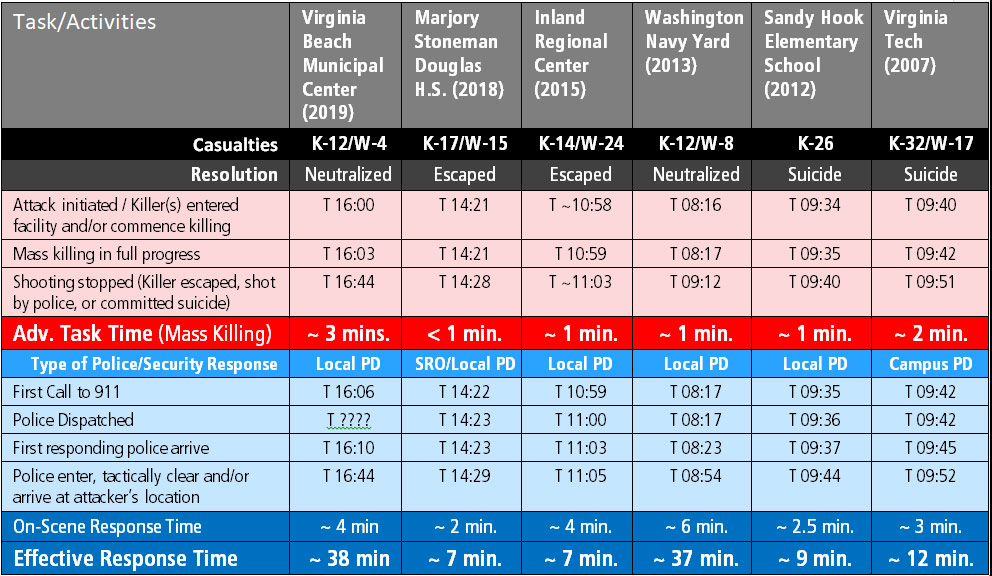

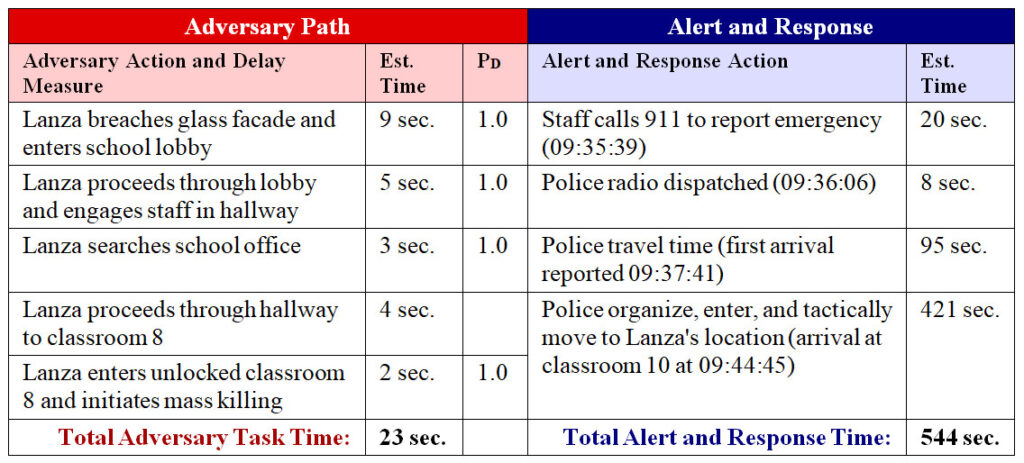

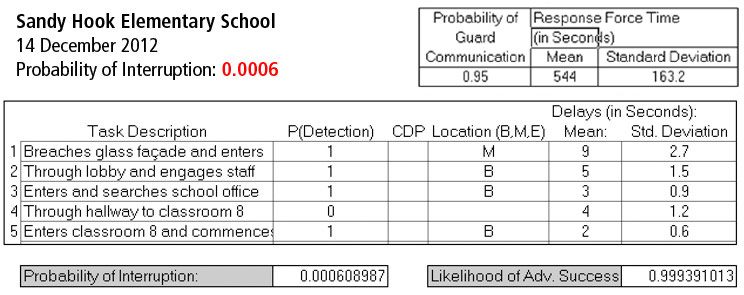

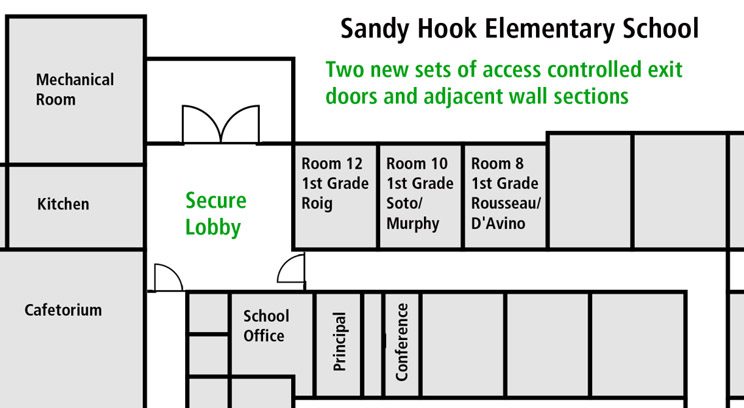

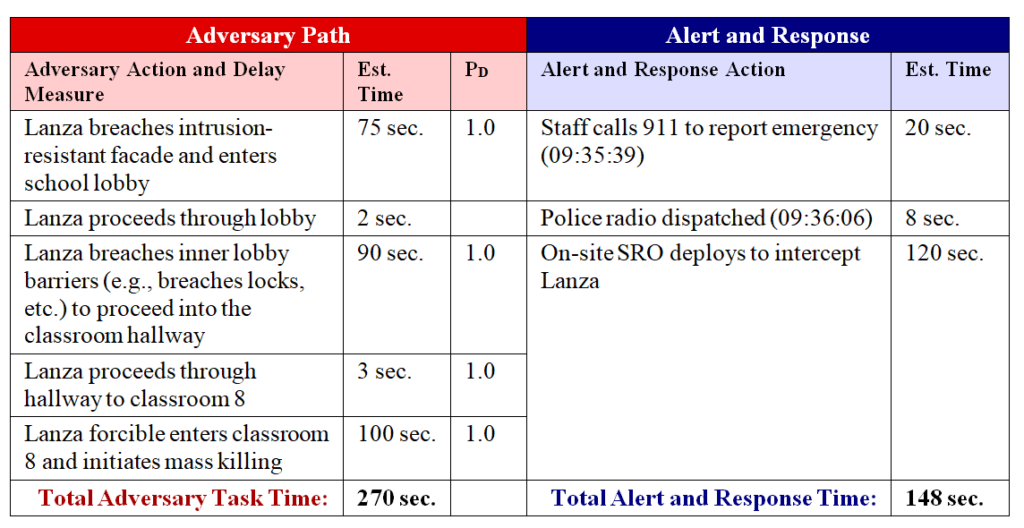

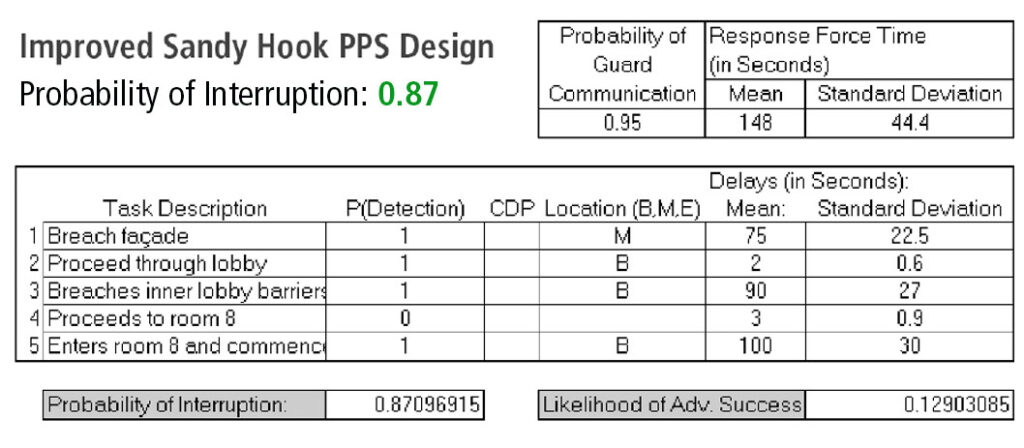

The concerns I’m describing are not hypothetical. We’ve had a number of shooting events where doors equipped with classroom-function locks remained unlocked due to these reasons. A few examples of incidents where this situation clearly contributed to unnecessary casualties include the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary shooting and 2007 Virginia Tech attack.[i] [ii] In those two events alone, 26 students and faculty were killed and 24 wounded specifically because of difficulty locking these doors.

By specifying “office-function” locks which feature a button or thumb turn, we can eliminate all these concerns.

Now here’s the question posed by the reporter…She asked if the ease of locking doors with “office-function” locks could be exploited by an attacker to barricade themselves inside a classroom to delay entry by police (as originally suspected in aftermath of the Robb Elementary School shooting).

And the answer is absolutely yes.

Although this situation is not common, we have had a number of events in the past where gunmen locked and barricaded themselves with victims to delay intervention by authorities. As a few examples:

- In 2019, a student perpetrator removed the magnetic strip covering a strike plate to lock a classroom door when he and another shooter opened fire on fellow students at the STEM Highlands Ranch School.

- In 2007, SHC used chains and a padlock to secure the exterior doors of Virginia Tech’s Norris Hall. A similar situation also occurred involving a chain and padlock at the Irvine Taiwanese Presbyterian Church in 2022

- In 2006, CCR boarded up the doors and windows during the West Nickel Mines school massacre.

In each case, the objective of the perpetrator was to delay intervention by authorities.

Another related concern is the issue of access-controlled door locks and potential interference with entry when police arrive on scene. This matter contributed to access complications during the 2015 attack at the Inland Regional Center in San Bernardino. And during the 2013 Washington Navy Yard shooting, police required use of an access badge recovered from a deceased security officer to enter secured areas of the building.[iii]

Now returning to the news interview, the implied question was if it would be better to have classroom function locks and weak barriers that can be easily breached by responding police.

And the answer is absolutely not.

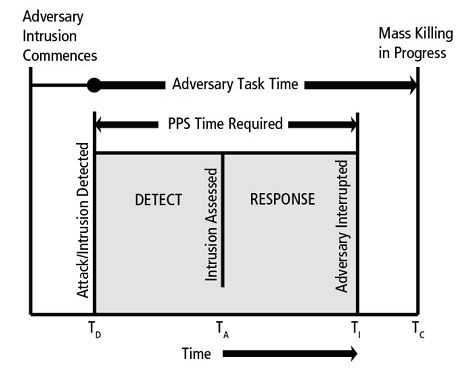

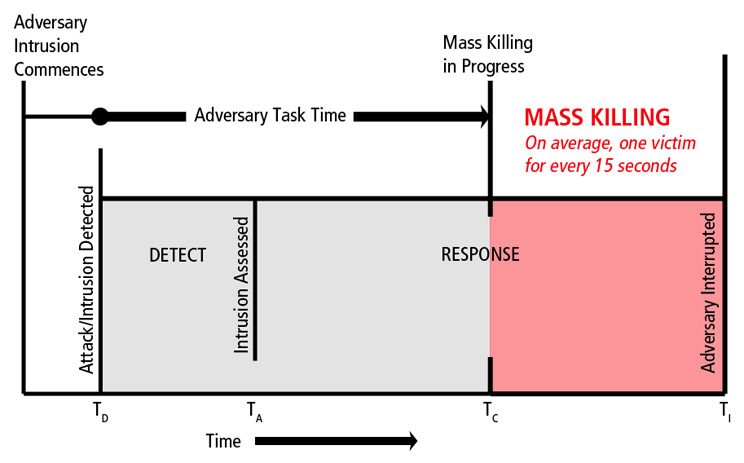

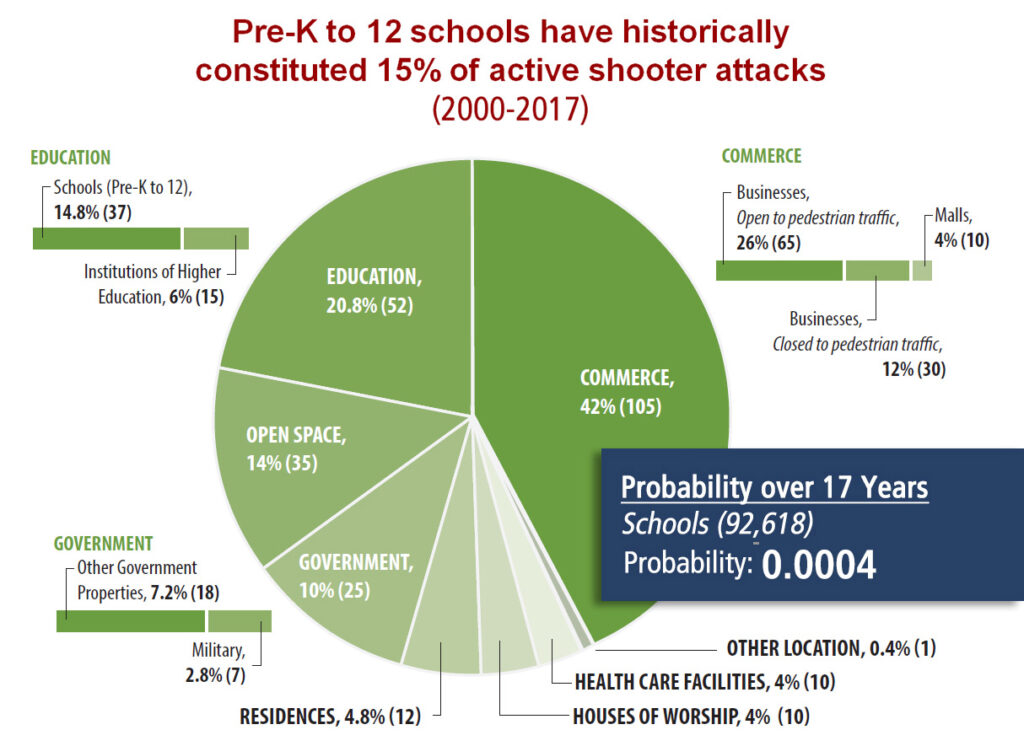

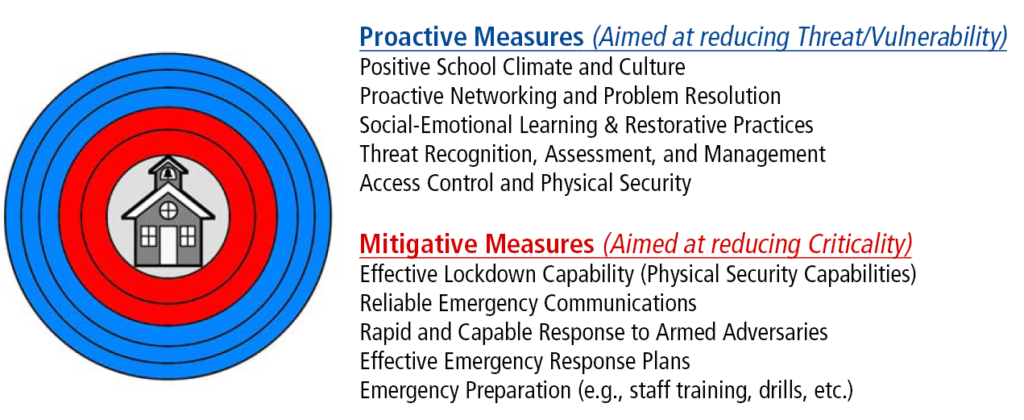

Although a gunman can easily lock an office-function lock without a key and access-controlled locks can complicate police entry, the importance of reliable door locking and building security greatly supersedes this concern. Bottom line, we need to effectively delay the bad guy while also expediting armed response. Those are both universal priorities in security design against active shooter violence.

To address concern about law enforcement access into secured buildings, there are approaches for dealing with that problem without compromising effective security.

First, all door locks to rooms where people may take refuge should ideally be keyed on a building or campus-level master key. Although distribution of master keys to employees should be carefully restricted, several master keys should be kept on rings and secured in a location reliably accessible to arriving police. This location can include a Knox Box or go-bag stored in a safe location outside the building (such as a security gate house). Likewise, if the facility employs an access control system with badge readers, an access badge with full privileges should be attached to each master key ring.

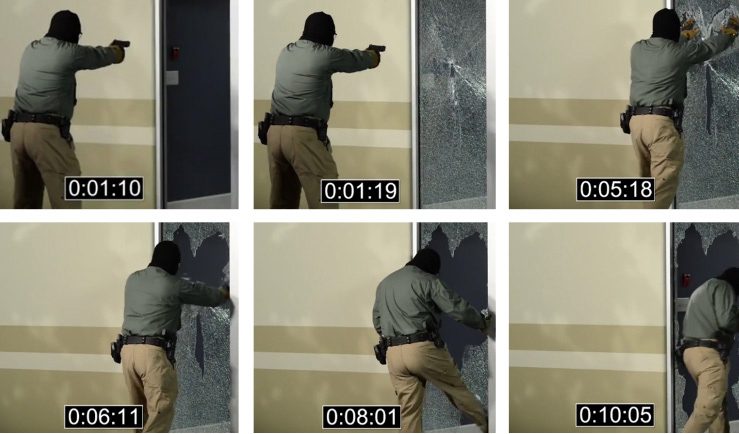

As for concern about chained doors and police access through intrusion-resistant barriers (e.g., windows, etc.), many police departments now equip patrol units with bolt cutters, Halligan tools, and simple breaching aids specifically for this purpose.

However you decide to approach this matter, please do not ever compromise barrier performance for fear about impaired police response. As an old saying goes, that’s a “cure far worse than the disease.”

References

[i] Report of the State’s Attorney for the Judicial District of Danbury on the Shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School and 36 Yogananda Street, Newtown, Connecticut on December 14, 2012. Office Of The State’s Attorney Judicial District Of Danbury, Stephen J. Sedensky III, State’s Attorney, N.p., 25 November 2013. pp.18

[ii] Mass Shootings at Virginia Tech. April 16, 2007. Report of the Review Panel. Virginia Tech Review Panel. August 2007. pp.13.

[iii] After Action Report Washington Navy Yard, September 16, 2013. Internal Review of the Metropolitan Police Department, Washington, D.C. July 2014. pp. 17.