Lessons Learned from Staring into the Abyss: An analysis of the Al-Noor Mosque Video

Examining active shooter behavior and identifying security vulnerabilities and failures during attack events is a critical part of improving our preparation for future violence. While recently updating case studies for a training program and working on a separate client project, I spent considerable time watching and re-watching live stream videos and CCTV footage from several previous attacks.

After getting past nausea and the psychic weight of watching such horror – a matter that never gets easier despite how many years I’ve been doing this – a number of lessons were evident that I thought worth exploring as the focus of an article. However, instead of surveying all of the incidents I case studied recently, I’ll limit our examination in this article to the 2019 Al-Noor Mosque shooting in Christchurch.

Attack Events and the Al-Noor Mosque Video

For those unfamiliar with this incident, the Al Noor Mosque is an Islamic worship center in the Riccarton suburb of Christchurch, New Zealand. On 15 March 2019, approximately 190 people were present during the time of the massacre. The attack was perpetrated by a white supremacist we’ll refer to in this article as “B.T.” The attack was streamed for exactly four minutes on Facebook Live beginning as he approached the mosque in his vehicle and ending after he exited the mosque and shot at a person on the street.

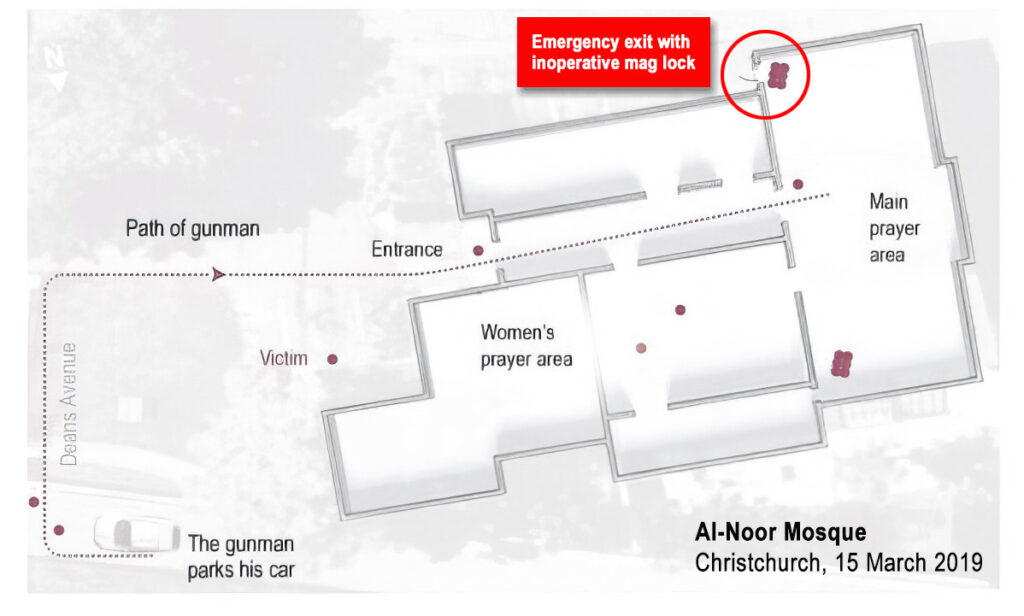

The attack commenced at approximately 1:40 pm during afternoon prayers. In the video, B.T. approaches the area while driving and parks on a street adjacent to the mosque. He then exits the vehicle dressed in tactical gear armed with an AR-15 style rifle and retrieves an additional shotgun from the back of his vehicle. At that point he proceeds down the road and onto Deans Avenue proceeding toward the entrance of the mosque’s walled courtyard.

Once inside the courtyard, he proceeds directly toward the main entrance where he fires multiple shots from the shotgun and kills two people standing in the doorway. After emptying the shotgun, he switches to an AR-15 style rifle equipped with a strobe light and continues directly toward the main prayer hall, firing at people in the hallway and through the doorway into the women’s prayer room.

As he arrives inside the main prayer hall, he begins firing at masses of people congested near the hall’s North and South exit doors. Both groups collapse into piles as people take cover, trip, and fall to gunfire. At this point, a man rushes toward B.T. and is shot and killed at close range.

B.T. then proceeds back into the hallway, reloads, and then returns to the main prayer hall where he begins firing into the piles of people still located near the exits. After firing several shots, he has a weapons malfunction. He clears the weapon, reloads, and continues firing intermittently at immobile people on the ground.

After exhausting all targets, he exits the mosque and heads toward the courtyard entrance while reloading again. When he arrives on the street, he fires several rounds at a pedestrian and the video ends.

Observations & key takeaways from the Al-Noor Mosque Video

1. B.T. arrived at the mosque armed with an arsenal.

In the video, multiple weapons can be seen in the back of B.T.’s vehicle. Media reports state that B.T. had six weapons altogether including two AR-15 style rifles, two shotguns, a handgun, and a bolt action rifle. And this situation is not uncommon. Many perpetrators of active shooter attacks arrive as if prepared for war, armed with multiple weapons and an extraordinary amount of ammunition.

As a practical implication of this point, security and police officers assigned to protecting venues against active shooter violence must be prepared for engaging a well-armed adversary. And with 5.56mm and 7.62x39mm weapons being frequent and having the greatest penetration capability of common weaponry, body armor worn by protective personnel should be rated NIJ Level III as a minimum. Likewise, when specifying bullet resistant materials, minimum specifications should be UL 752 Level 7 (5.56mm x 5 shots) and EN 1063 BR5 (5.56mm).

2. B.T. proceeded straight to the main entrance of the mosque and did nothing to conceal his approach.

As discussed in other Expert Insight articles, a significant percentage of attacks by outsiders commence outdoors and progress indoors. Likewise, outside attackers usually enter directly through main entrances (as opposed to auxiliary entrances and exits).

As a first practical point, early detection of an approaching attacker while he/she is outdoors is crucial in providing an opportunity for building lockdown and initiating emergency alert. One way this can be accomplished is by posting security personnel outdoors with view of possible approach points. When working with houses of worship as a consultant, I often advise posting security personnel and/or volunteer greeters outdoors equipped with radios for this purpose.

As we’ve also witnessed in many other attacks, B.T.’s first rounds were shot outdoors before he made entry into the building. In these type of situations, gunshot detection systems can be invaluable and often integrated with an access control system to automate lockdown of access controlled exterior doors.

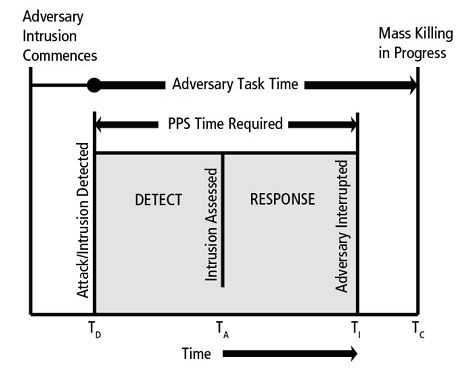

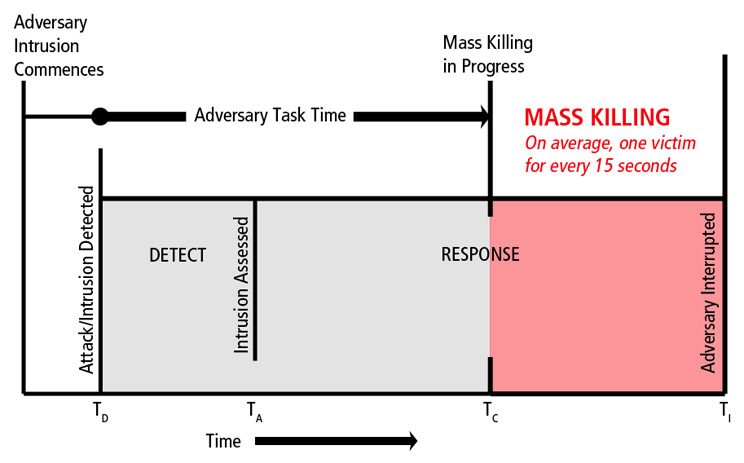

3. The total time from when B.T. arrived on site (entered the courtyard gate) to when mass killing was in full progress (inside the prayer hall) was 30 seconds.

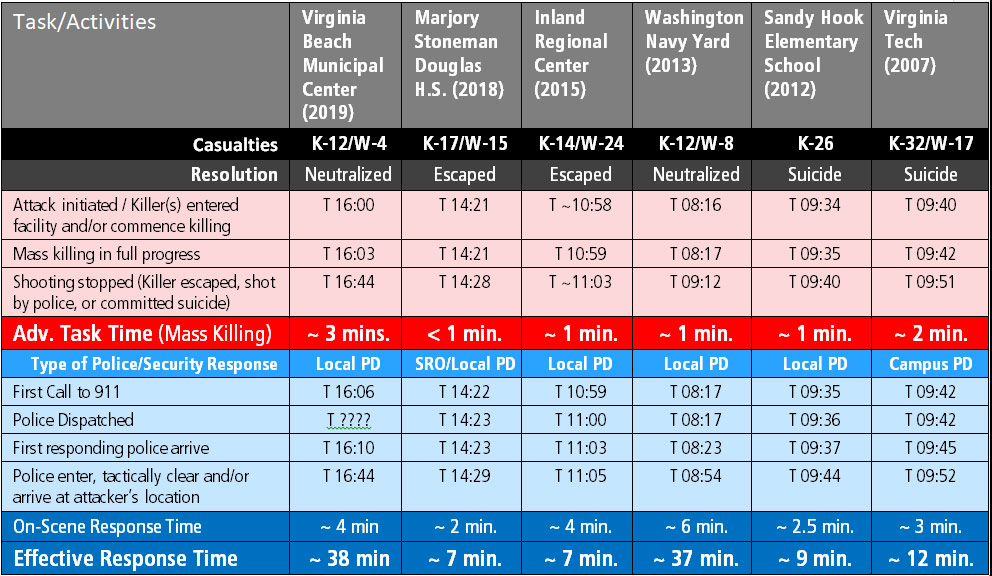

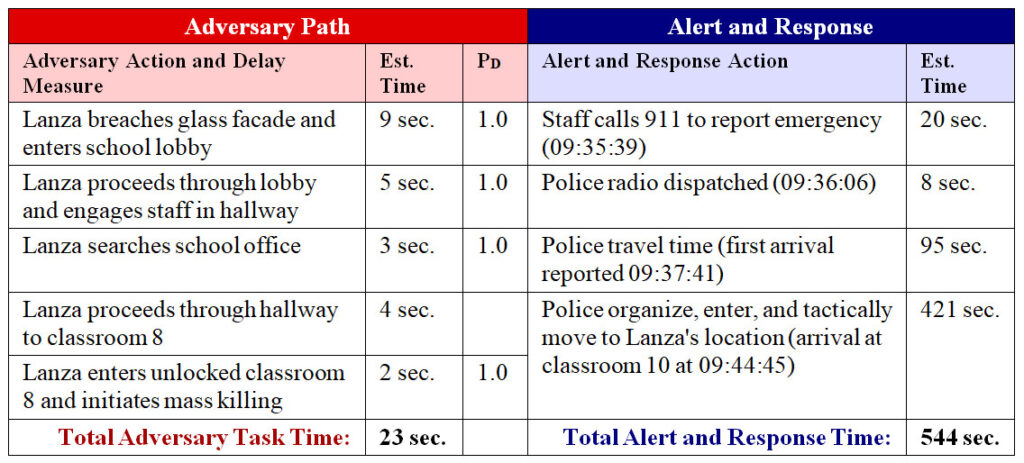

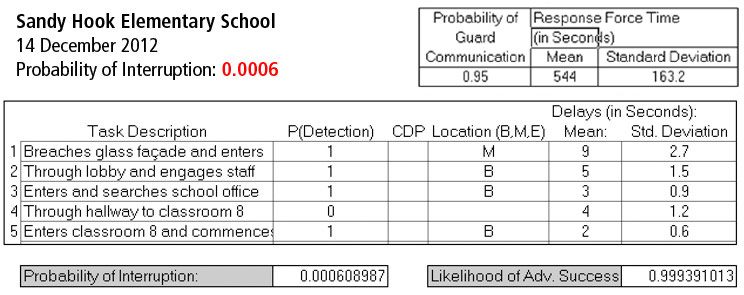

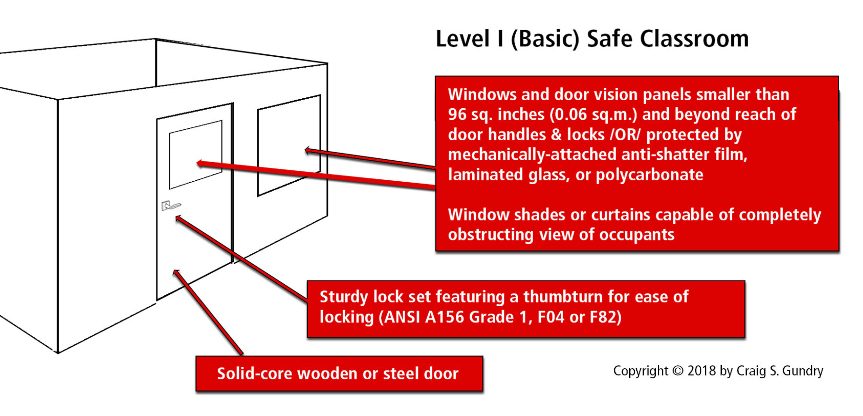

As we’ve discussed in previous articles, these events go down FAST and the variance between adversary task time and response time in these incidents has a direct correlation with the degree of tragedy. At the Al-Noor Mosque, the absence of detection and delay elements (e.g., intrusion-resistant doors, glazing, etc.) resulted in minimal opportunity for people to initiate a protective response.

To provide further perspective on this matter, B.T. killed 41 people and wounded 40 in a total time period of 107 seconds (from first shot on approach to the last shot inside the mosque).

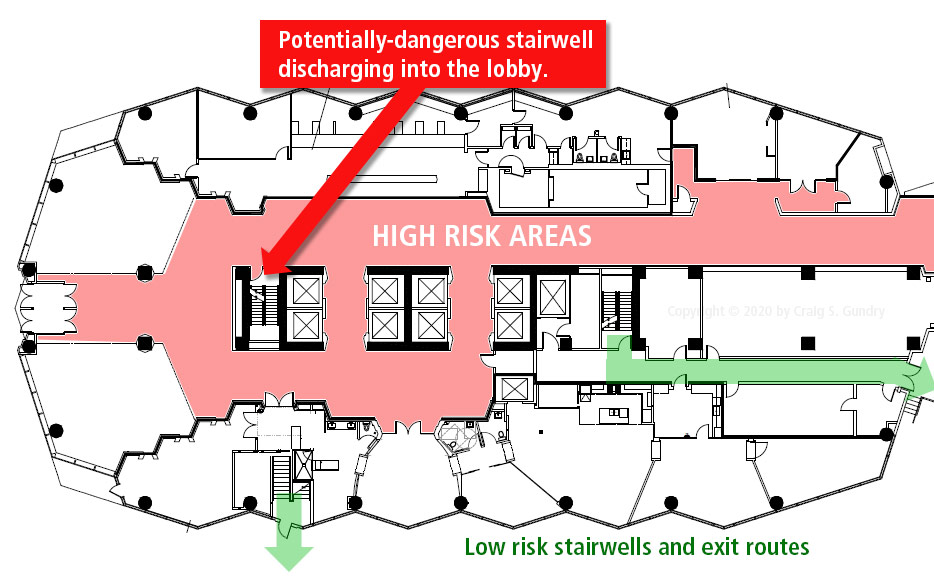

4. Most people were killed while bottle-necked at the two exit doors inside the prayer hall.

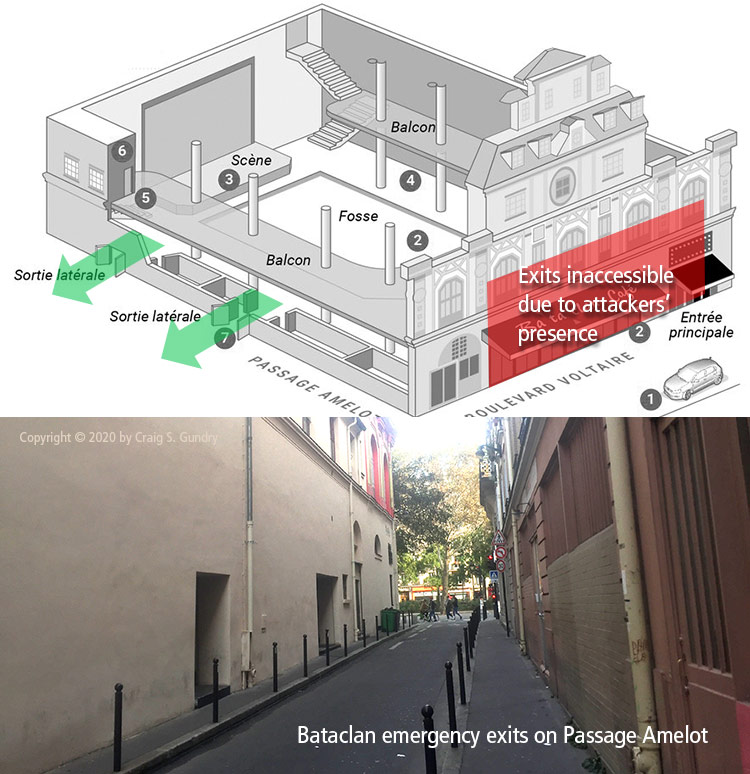

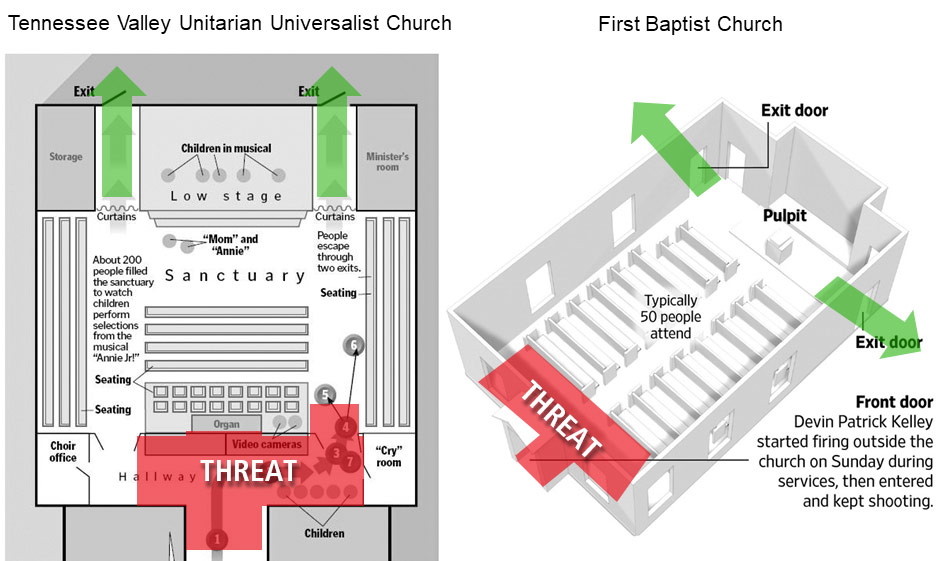

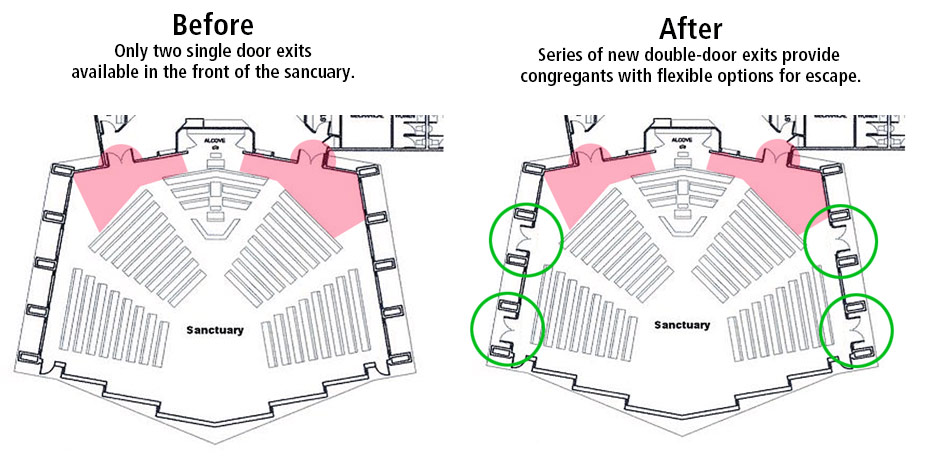

Minimal escape options and limited exit capacity are common problems in group assembly areas. And this unholy combination of conditions has contributed to significant casualties in a number of incidents. In addition to the Al-Noor Mosque, other examples include the shootings at the First Baptist Church (Southerland Springs, 2017), the Bataclan Theater (Paris, 2015), Pulse Nightclub (Orlando, 2015), and the Reina nightclub (Istanbul, 2017).

Unfortunately, egress design is a frequently overlooked matter in active shooter preparation. Please see my other article focusing on egress design and active shooter attacks for a more detailed examination of this issue and options for remedy.

5. Compounding the egress problem, people at the South exit door were trapped because of inability to disengage a mag lock.

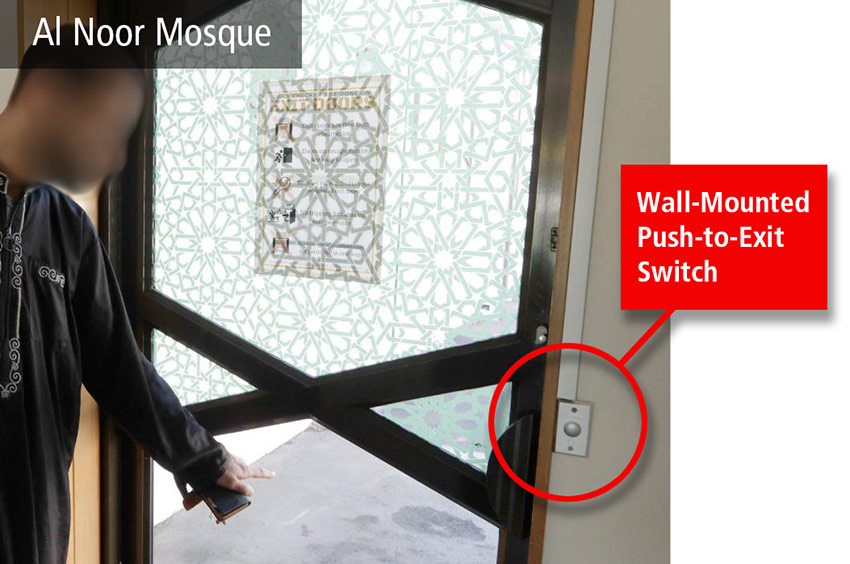

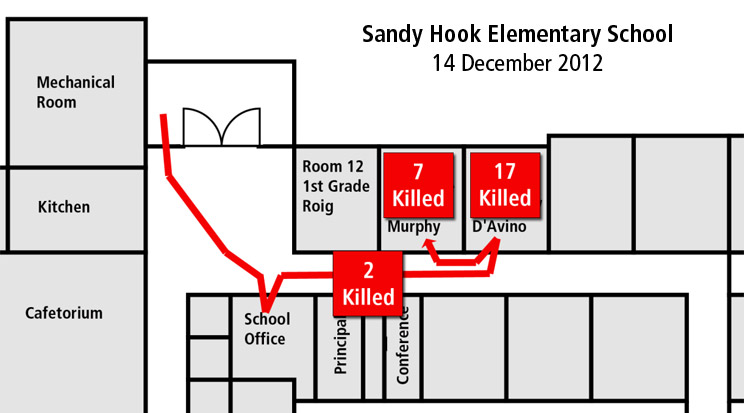

When B.T. begins firing inside the main prayer hall, a large group of people can be seen amassed near the exit on the south side of the mosque. It’s not evident in the video, but those people were literally struggling for their life to open the locked exit door due to an electromagnetic lock and nondescript push-to-exit switch that no one could locate. Seventeen people died at that door as a result. In fact, those who survived broke through the glass door to escape.

NOTE: The position of casualties depicted in the above diagram is incomplete. However, the diagram does accurately depict the location of victims inside the main prayer hall.

As we’ve discussed on other articles, mag locks present a number of problems during active shooter attacks and should be avoided whenever possible. First, life safety codes universally require that egress doors equipped with mag locks fail safe (unlocked) during fire alarms. In this situation, the fire alarm is a ‘virtual master key’ and will compromise any door equipped with a mag lock. And although such situations are uncommon, we have had a number of attacks where fire alarms were activated by gunmen, good Samaritans, or indoor weapons fire.

Codes also require door-mounted exit hardware (e.g., switch, lever, etc.) or alternatively, an exit sensor to unlock mag locks when an alarm is not activated. At the Al-Noor Mosque, there was no exit sensor (only a push-to-exit switch). Although this was a violation of code and should never have been permitted, I’ve witnessed numerous situations in my consulting activities where previous fire inspectors overlooked this issue. I have also seen situations where facilities have taped over the exit sensors to avoid unintentional unlocking as people pass nearby (another common problem associated with mag locks).

As a much better alternative, I recommend using electrified exit bar devices or electric strikes with mechanical hardware on exit doors. During an evacuation, electrified exit bar devices operate identically to mechanical exit bars—push the bar and the door opens. Aside from ease of operation, doors equipped with electrified exit bars and electric strikes can remain secured during power disruption and fire alarms (withstanding stairwell doors and other situations as defined by code).

Recent Comments