The MSDHS Commission Report – A Security Expert’s Critique (2/2)

By Craig S. Gundry, PSP, cATO, CHS-III

Part One of this article surveyed concerns expressed by Critical Intervention Services regarding school ‘target hardening’ measures proposed by the MSDHS Public Safety Commission report. Part II continues with an examination of additional concerns worthy of potential consideration by the FDOE Office of Safe Schools.

Emergency Preparation Matters Weakly Addressed by the MSDHS Public Safety Commission Report

Pages 47-52 of the Commission report spotlight a number of failures in emergency response at MSD High School. One of these failures was the significant delay in public address alert. Unaware that an attack was in progress, approximately 100 students massed in the third floor hallway after a fire alarm was activated by Cruz’s gunfire on the ground level. Although most students in process of evacuating found refuge before Cruz arrived at their location, twenty students and three teachers were caught in the hallway when the onslaught began on the third floor.

The Commission report describes the absence of a district policy for active assailant situations and lack of recent training and drills as contributing factors to the delayed public address alert. On pages 84-85 (Section 3.1), the Commission proposes a number of measures to address these matters in addition to other conditions which contributed to the tragedy at MSD High School. Although CIS endorses all of the recommendations proposed in Section 3.1, there are a number of important issues addressed in general terms that would benefit from improved emphasis and specificity.

The recommendations on pages 84-85 state, “All staff should have clearly established roles and responsibilities that are outlined in a written policy and procedure manual provided to all personnel,” and, “Every district and school should have a written, unambiguous Code Red or similar active assailant response policy that is well known to all school personnel, parents, and students.” However, the Commission provides no specific recommendations for faculty training or improved guidelines for scheduling active shooter drills to remedy the vague direction of Florida Statute 1006.07(4)(a): “Drills for active shooter and hostage situations shall be conducted at least as often as other emergency drills.”

CIS recommends that Florida schools adopt the Guardian SafeSchool Program® standard for faculty training by mandating annual instruction in emergency procedures before the commencement of each school year in addition to active shooter drills. In our work with school clients, we typically present faculty training sessions as a two-hour program at the beginning of each academic year and whenever promulgating a new school Emergency Response Plan. Topics normally include an overview of the school’s emergency team structure, communications systems (including key notification and alert procedures), imminent threat response, reunification procedures, and a module on recognizing warning behaviors associated with targeted aggression.

Although the MSDHS Public Safety Commission report describes the need for campus-wide public address (PA) notification, the report offers little recommendation for the design of reliable PA system infrastructure. Many Florida schools do not have public address systems which can be used reliably under high stress conditions. Schools with analog public address systems often have base stations positioned in highly vulnerable locations such as main reception offices. Schools with analog public address systems should consider replacing these systems with modern IP‐based public address or phone systems which can facilitate emergency announcements from versatile locations throughout the school. Phone-based systems which require dialing an extension or entering a code to access the ‘all call’ function should be programmed with numbers that are easy to remember and simple to dial under stress (e.g., ‘111,’ ‘777,’ etc.). Additionally, all faculty members should be trained and fully empowered by policy to issue PA announcements when attack events are first recognized.

As another concern, many Florida schools do not presently have a mass notification system that can be reliably used to alert staff as a redundant mode of communication. Critical public address announcements should always be followed by a redundant message via digital mass notification system (MNS) for those who may not have heard the initial announcement. When important developments occur, updates can be issued to teachers as follow up messages. Circumstances warranting updates may include notification when police are clearing the building or if a unique threat emerges, such as a building fire.

Mass notification systems should be easy to use under stress and optimally feature pre‐configured messages for key alerts to minimize the time required to type and send messages. A good mass notification plan should also include facility‐wide Wi‐Fi access and employ a mass notification system with iOS and Android applications to facilitate Internet messaging in the event there are areas inside the structure with SMS signal interference.

As the FDOE Office of Safe Schools (OSS) progresses in 2019 toward developing best practices for Florida schools, CIS strongly recommends that the OSS promulgate guidelines for the development and performance of reliable emergency communications infrastructure.

To the credit of the Commission, we are glad to see the Level II recommendation: “Provide school personnel with a device that could be worn to immediately notify law enforcement of an emergency.” As we’ve discussed in other LinkedIn articles, any measure which simplifies and expedites alert to a response force (e.g., police, SRO, on-site armed security, etc.) has a noteworthy benefit in improving system performance.

Concerns Regarding Reconciling Security Needs with Negative Impact on School Climate

In 2014, the National Association of School Psychologists released a position paper expressing great concern over the implementation of high profile security measures on school climate and culture (two of the most important principles in creating a successful learning environment).[i] As support for their concern, the NASP paper cites a number of studies which outline the negative impact of high profile security measures in schools.[ii] [iii][iv]

Responsible approaches to school security design should carefully balance the risk of violence against potential negative impact on the school’s overall mission of providing good education. Beyond negative impact on the school’s educational mission, anything that suppresses positive school climate also directly conflicts with the objective of proactively reducing threat conditions.

In the context of school security, proactive risk management starts with reducing potential threat. This is first accomplished by reducing the potential conditions that contribute to advancement on the targeted violence pathway. Reinforcement of positive school climate, creating strong bonds between staff and students, mentoring students with problems, actively intervening in bullying situations, and restorative practices are all examples of measures aimed at reducing threat. All aforementioned measures reduce threat by creating an atmosphere where social marginalization is discouraged, bullying is not tolerated, and students feel trust in reporting student behaviors of concern. Considering the high frequency of leakage (communication of violent intent to a third party) in advance of attacks by students, the US Secret Service and National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime have repeatedly emphasized the importance of school climate in breaking the classroom ‘code of silence.’ [v][vi]

High profile security measures and haphazard implementation can easily frustrate this effort. As stated by K.C. Poulin, the CEO of CIS, “If you make an environment feel like a prison, don’t be surprised when the community members feel and act like inmates.”

To address these concerns, school security programs should be specifically engineered to create “invisible” layers of prevention and preparedness that are largely unnoticed by students. This low-profile approach should be consistent in all aspects of the program, from procedural design to physical security measures.

Regretfully, there are aspects of the MSDHS Pubic Safety Commission’s recommendations and the provisions of Florida’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act which overlook the importance of potential impact on school climate.

As a Level III recommendation, page 349 states: “Metal detectors and x-ray machines at campus entrances.”

Although metal detectors are commonly used in urban school districts historically plagued by youth gun crime, this measure is often counter-productive to security (proactive threat reduction via positive school climate) and operationally burdensome. First, studies of the use of metal detectors in schools have demonstrated inconclusive results in reducing violent behavior among students.[vii][viii]

In regard to school climate, the use of metal detectors boldly communicates distrust in the student population and potentially reinforces the ‘wall of psychological/social separation’ further between students and the administration. Measures that communicate distrust to the general student population directly counter our greater aim of creating an atmosphere where threat activity witnessed by students is likely to be reported.

In addition to the concern about impact on school climate, schools that opt to implement screening with metal detectors and x-ray machines should carefully assess the costs and operational requirements before committing to this measure. Throughput rate alone is a serious issue of consideration. Walkthrough metal detectors typically have a throughtput rate of 15-25 people per minute.[ix] X-ray machine operators can typically scan 10-20 objects per minute.[x] With these general throughput rates in consideration, it would take a single-lane inspection station 75-150 minutes to process a high school of 1,500 students arriving for class. Even if two x-ray stations were employed with a single metal detector, it would only improve throughput rate to 60-100 minutes. Additional considerations include space requirements for screening stations and cueing lines at campus entry points, staffing and personnel training, financial cost of equipment ($30,000+ for x-ray machines alone), maintenance, etc. Achieving any level of practical efficiency would require significant investment and operational burden or compromised effectiveness by limiting screening to a subset of students.

CIS recommends that metal detectors and x-ray screening be reserved for situations where there is a clear cost-benefit advantage (such as schools in locations where gun crime is a persistent problem).

The Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act’s Coach Aaron Feis Guardian Program requires that candidates complete 132-hours of firearm safety and proficiency training, psychological evaluation, drug tests; and complete certified diversity training. However, there are no training requirements related to interpersonal relations skills, social network development, conflict resolution, targeted violence behavior, threat assessment methodology, or other critical school security topics such as emergency response.

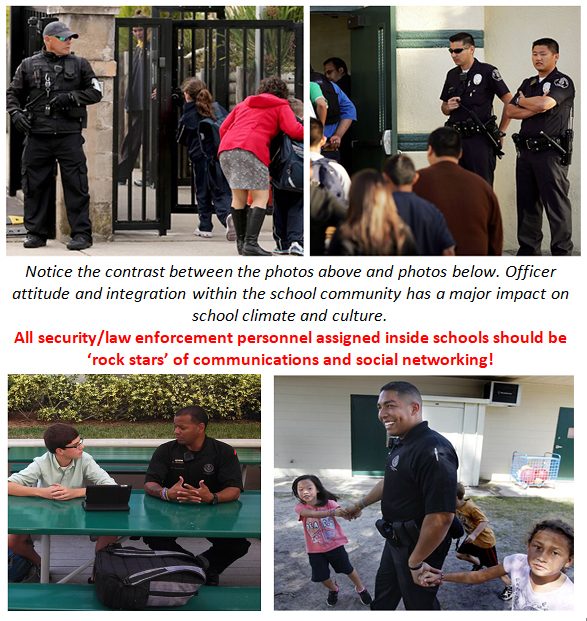

Several Florida school districts (e.g., Broward, Hillsborough, etc.) have opted to employ armed security officers in some schools rather than utilize employee Guardians or School Resource Officers (SROs). However, none of these districts have implemented specific measures to recruit and train candidates with superior communication skills and proven ability to work with youth in school environments. This problem also extends to law enforcement agencies throughout the state in the selection of personnel for School Resource Officer programs. Unfortunately, few law enforcement agencies incentivize officers with exceptional combination of both tactical and interpersonal communications skills to join SRO programs. Rather, SRO programs are often culturally‐viewed within police departments as a demotion from road duty and other special units. SRO programs which emphasize the officer’s role as ‘law enforcer’ within the school also risk further social division between students and the administration.[xi]

In most schools, the most visible element of the security program will be the School Resource Officers, Guardians, or security officers assigned to the school. To counter any negative impact of their presence, officers should be specifically selected and trained to actively develop relationships and positive rapport within the school community.

Craig Gundry

Copyright © 2019 by Craig S. Gundry, PSP, cATO, CHS-III

CIS Guardian SafeSchool Program® consultants offer a range of services to assist schools in managing risks of active shooter violence. Contact us for more information.

References

[i] Research on School Security. The Impact of Security Measures on Students. National Association of School Psychologists. N.p. 2014.

[ii] Phaneuf, S. W. Security in schools: Its effect on students. El Paso, TX: LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC. 2009.

[iii] Bracy, N. L. (2011). Student perceptions of high-security school environments. Youth & Society, 43, 365-395.

[iv] Schreck, C. J., & Miller, J. M. (2003). Sources of fear of crime at school: What is the relative contribution of disorder, individual characteristics and school security? Journal of School Violence, 2, 57-79.

[v] OToole, Mary Ellen. The School Shooter: a Threat Assessment Perspective. FBI Academy, 2000

[vi] Fein, Robert A. Threat Assessment in Schools: a Guide to Managing Threatening Situations and to Creating Safe School Climates. United States Secret Service, 2004.

[vii] Hankin, A., Hertz, M., & Simon, T. (2011). Impacts of metal detector use in schools: Insights from 15 years of research. Journal of School Health, 81, 100-106.

[viii] Casella, R. (2006). Selling us the fortress: The promotion of techno-security equipment in schools. New York: Routledge.

[ix] Green, Mary. The Appropriate and Effective Use of Security Technologies in U.S. Schools. A Guide for Schools and Law Enforcement Agencies. U.S. Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs. Washington, DC. 1999. pp. 70.

[x] Ibid. pp. 95.

[xi] Nemeth, Charles. J. Peer Review Report of CIS Guardian SafeSchool Program® Officer Model. John Jay College of Criminal Justice. Center for Private Security and Safety. New York, NY. 2014.