Active Shooter Response Training: Important tips for preparing employees in an effective and responsible manner

It’s an obvious point that even the best-designed response plans and facility preparations will be of limited benefit if employees are unprepared to take independent action for their self-preservation during active shooter attacks. In recent years, recommendations and guidance from a number of authoritative sources (e.g., Department of Homeland Security, ASIS International’s WVPI-2020/AA, etc.) have progressively established a ‘standard of care’ expectation for active shooter response training in workplace settings.

Although these authoritative sources universally promote the importance of training employees and establish a basis for response doctrine (“Run-Hide-Fight”), there is little empirical guidance regarding effective and responsible practices for employee training beyond NASRO-NASP’s Best Practice Considerations for Armed Assailant Drills for Schools published for the educational community.

In the absence of universally recognized standards for active shooter response training outside the educational community, numerous instructional approaches and “branded training systems” have emerged with practices ranging from instructing employees to watch a 5-minute video to conducting aggressive scenario-based drills involving a role player hunting and shooting employees throughout the office with high-velocity paint projectiles. The consequences of this “Wild West” type situation only became fully clear to me when I was hired last year as an expert witness in a liability case involving a traumatized employee who incurred an injury during an active shooter drill.

In the absence of a recognized body of “best practices” for conducting active shooter response training, the following are some tips for designing and conducting active shooter-related training programs that address a number of common shortcomings and problems we witness out there in the Wild West today.

Instruction during active shooter response training should clearly empower employees to take independent action during possible attack events

During most emergency situations in workplace settings (e.g., severe weather events, building fire, bomb threats, etc.), there is often time and opportunity for an Incident Commander to initiate an alert and floor/zone captains or work supervisors to safely organize and direct employee response. By contrast, during active shooter events, every second is critical and any hesitation by employees while awaiting instructions can be fatal.

Keep in mind, emergency communication plans often fail during active shooter attacks. In some cases, this is due to a lack of situational awareness or the inability of emergency team members to safely access public address systems. In other cases, it may be due to “freezing” in response to life-threatening danger or the impairing effects of the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) on memory recall and problem-solving ability. As a result, emergency public address announcements are often delayed (if they occur at all). A few examples of this situation include the attacks at Sandy Hook Elementary School (2012), Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School (2018), Robb Elementary School (2022), and The Covenant School (2023).

To address this matter during classroom training, we begin discussion about active shooter response with a slide specifically dedicated to attack recognition followed by a bold-formatted statement: “Do not wait for someone to tell you what to do!”

I’ll often reinforce this point further with a few examples from previous attacks illustrating people who recognized potential danger based on limited information, trusted their instincts, and survived by taking action for their personal safety without further instructions.

Keep the principles of active shooter response simple during training while also ensuring employees understand the dynamics of different situations and choices.

It’s assumed that most reading this article are familiar with the DHS active shooter response training doctrine based on the terminology “RUN-HIDE-FIGHT.” This simplified response guidance is designed to be a prioritized list of preferred protective responses when an active shooter attack is recognized. “RUN,” for instance, should always be the first option when the opportunity is present. If RUN is not possible, then “HIDE” is the next prioritized option. And last, if there is no option to RUN or HIDE, employees should use whatever force is available to protect themselves and others if caught in close proximity of a gunman (“FIGHT”).

Although RUN-HIDE-FIGHT is easy to remember, it doesn’t clearly describe the safest actions in many situations. Instead, we prefer a different terminology in our active shooter training programs using the terms ESCAPE, BARRICADE, and DEFEND.

First, the DHS term “RUN” simply implies moving away from danger at a fast speed. Often this is good advice, but can also be dangerous if the employee doesn’t have accurate situational awareness of the location of danger. Our preferred term “ESCAPE” may mean running. ESCAPE may also mean moving cautiously while sensing the environment for the location of danger. ESCAPE also considers non-conventional methods of getting away from danger such as moving to the roof (if accessible) or climbing out a window.

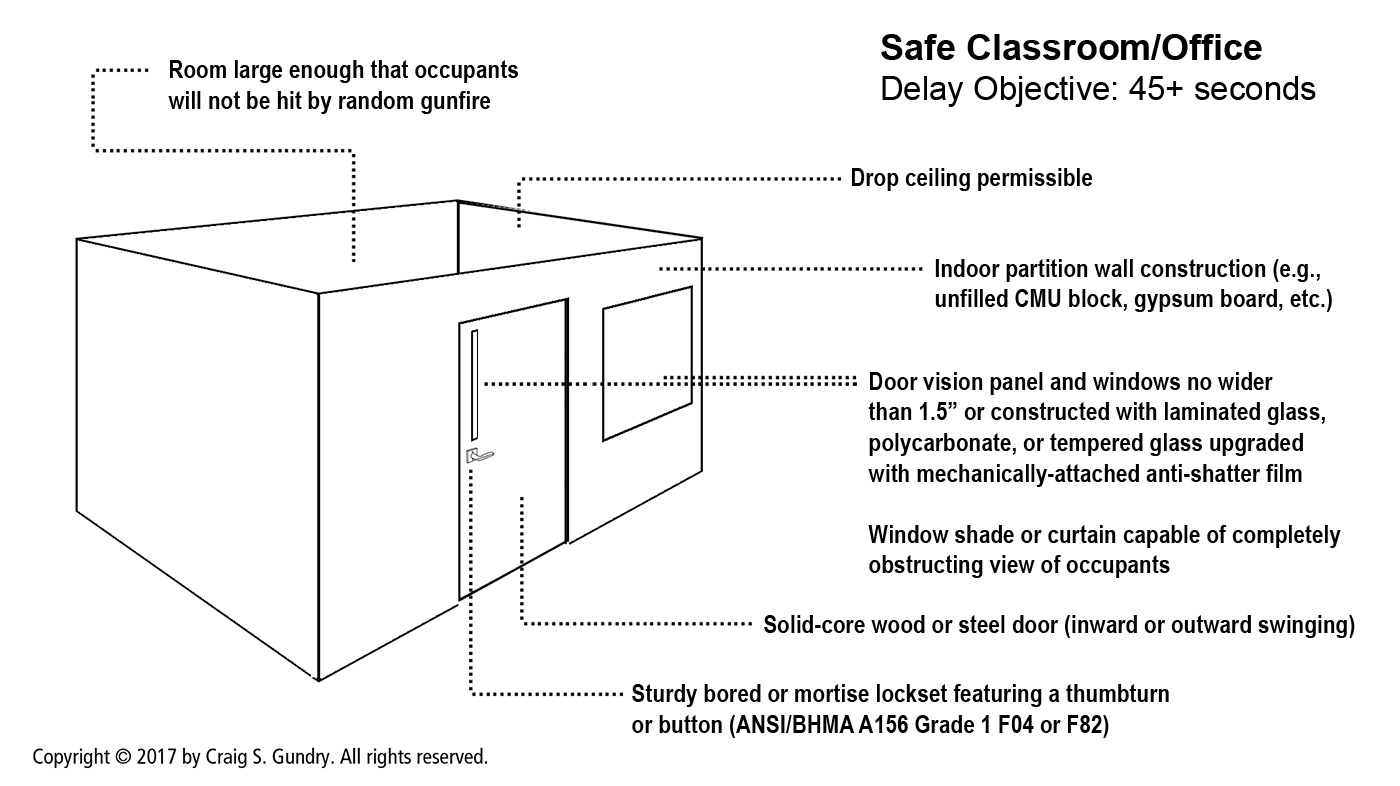

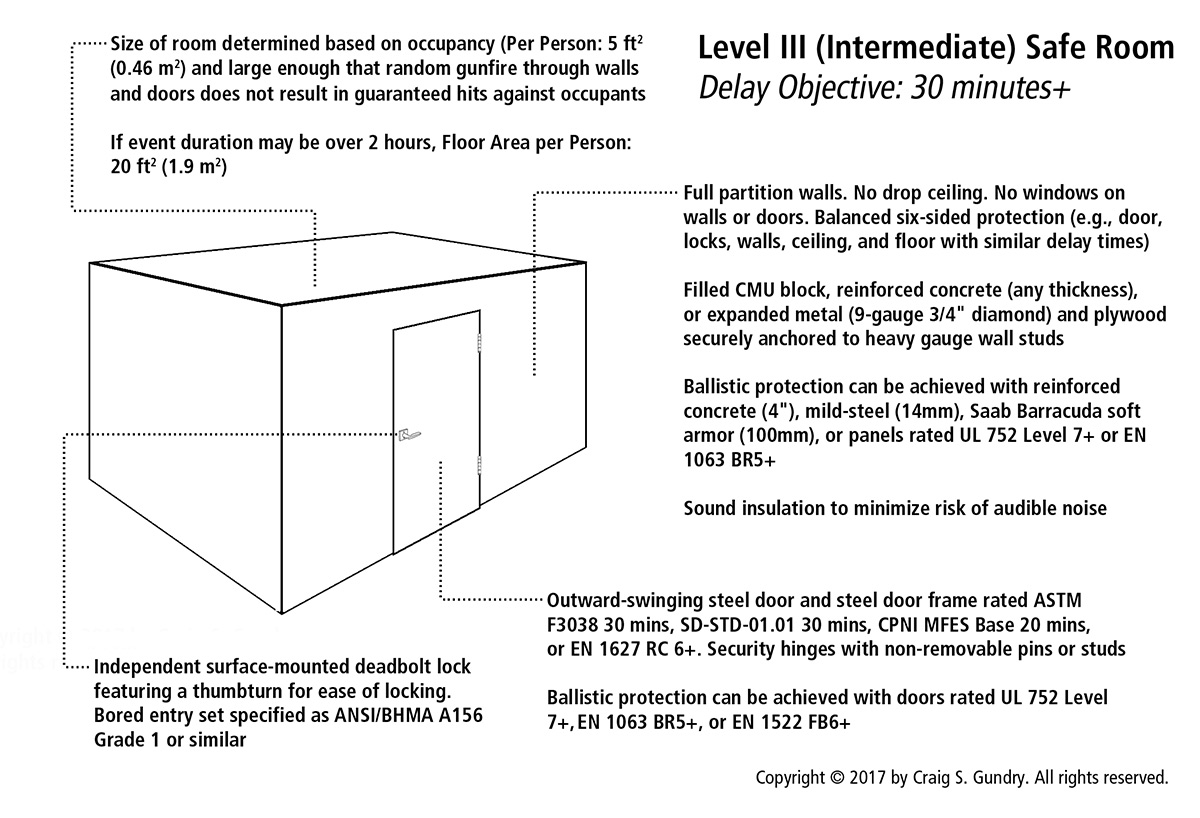

Likewise, the DHS term “HIDE” simply implies concealment. We want to emphasize to employees that the only truly safe location to seek refuge during an armed attack is an intrusion-resistant room that can be properly secured. If ESCAPE is not an option and there is no safe location nearby to seek refuge, hiding is better than nothing. But it is still unsafe.

Our preference for the term “DEFEND” over the DHS term “FIGHT” is for reasons of psychological acceptance. The word “FIGHT” is often interpreted offensively and many employees impulsively recoil at the idea of taking offensive action against a gunman. The term DEFEND is less provocative and easier to psychologically justify.

With a similar aim of communicating preferred response actions in a simple manner, the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Center employs the acronym “ADD” (AVOID-DENY-DEFEND). Other training systems employ more complex acronyms like ALICE (ALERT-LOCKDOWN-INFORM-COUNTER-EVACUATE) and A.L.I.V.E. (ASSESS- LEAVE-IMPEDE-VIOLENCE-EXPOSE).

Regardless of the terminology used, ensure that employees also understand that the safest action in one situation may be dangerous in another depending on where the attacker is located in relation to the employee, building geography, presence of nearby safe refuge rooms or exits, etc. Although our aim is to present response actions in a simple manner that’s easy for employees to remember, it’s also important that employees understand what types of circumstances may warrant a preferred response.

Customize the active shooter response training program to ensure that employees understand how the principles of response relate to their specific workplace environment

Prior to conducting any active shooter response training, I recommend conducting an assessment to ensure that the physical conditions and communications infrastructure at the facility are adequately ready to support the expected response of employees during active shooter events. Likewise, it is important that instructors are familiar with the facility’s communications systems, egress capabilities, and safe refuge options as necessary for relay to participants during training sessions and answering questions about conditions specific to the facility.

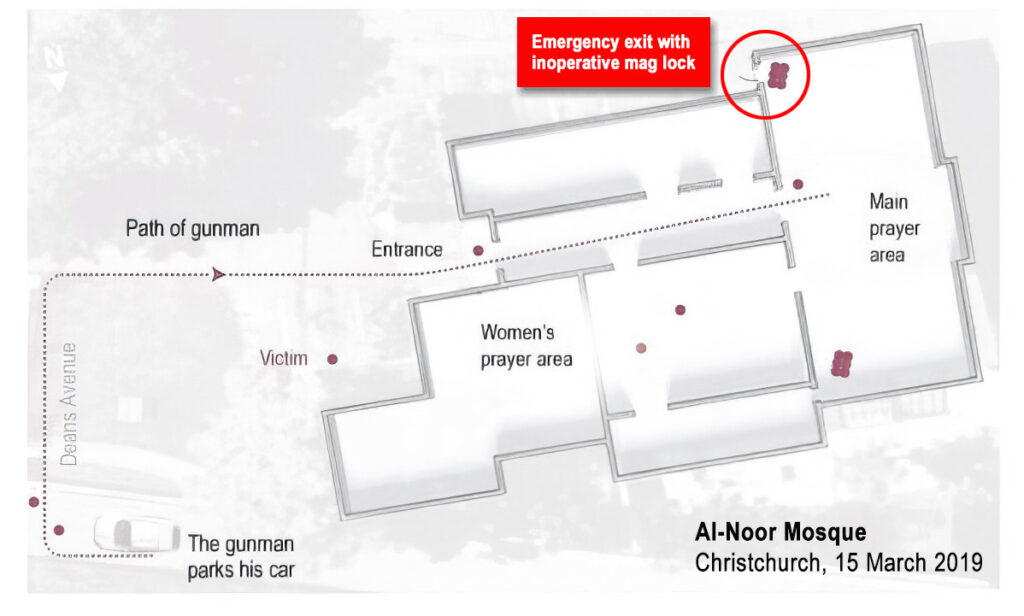

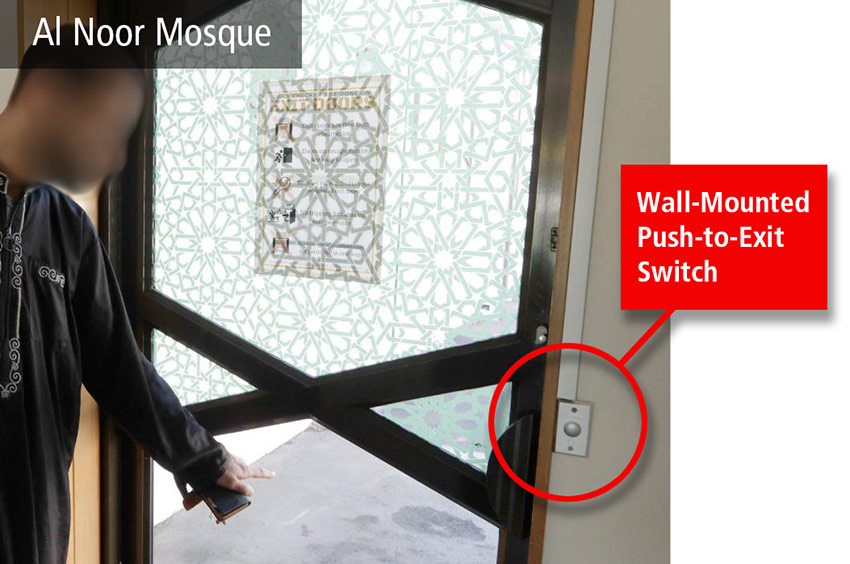

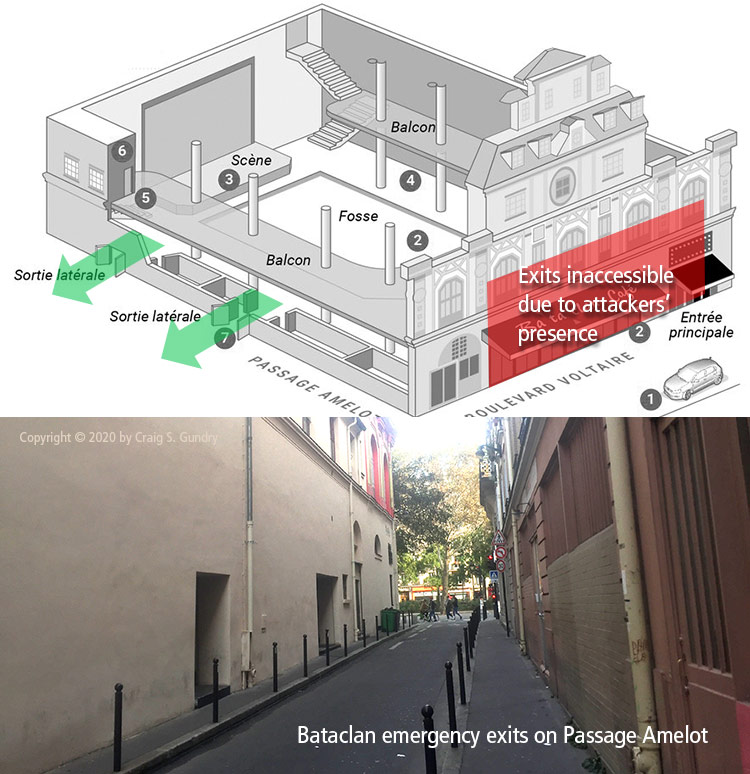

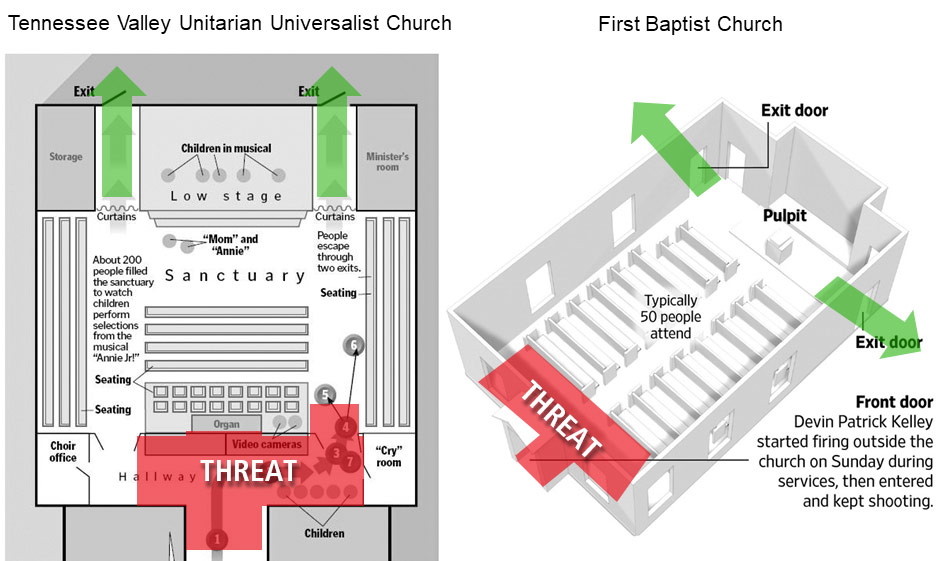

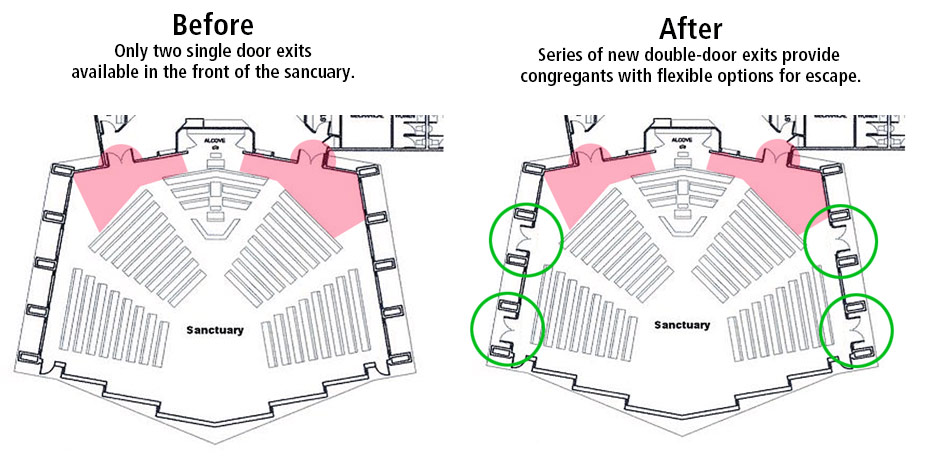

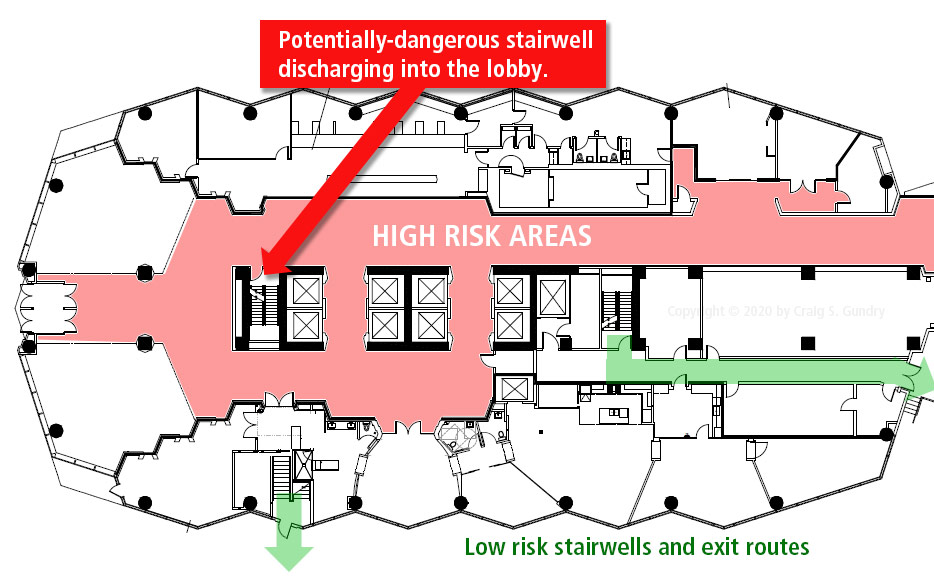

When discussing ESCAPE (DHS “RUN”) as a response, display a floor plan of the facility and its exits to identify suitable egress options and identify any exits that should be regarded as dangerous (e.g., stairwells that discharge into first-level lobbies or corridors, etc.). Similarly, if there is an accessible roof access, identify its location on the floor plan and make note of how to access the roof during the presentation.

When discussing BARRICADE (DHS “HIDE”) as an option, display a slide with a floor plan identifying all rooms on each building floor that meet safe refuge criteria (accessible, intrusion-resistant rooms that can be reliably locked by employees). If there are no rooms that meet safe refuge criteria, be sure to clearly make that point to employees and emphasize that ESCAPE is the only truly safe response in this situation.

In addition to discussing facility characteristics as related to active shooter response, I also recommend including a description of procedures for making an emergency ‘all-call’ announcement using the facility’s phone system (if programmed accordingly) or mass notification system if present (e.g., Informacast, etc.).

Reinforce memory through physical and/or mental engagement

As mentioned earlier in this article, the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) is often activated during life-threatening situations with impairing effects on memory recall and problem-solving ability. As a result, it’s often no surprise when employees who simply listened to a classroom lecture or watched a video about active shooter response forget critical safety measures, freeze, or take irrational actions when challenged months later during a real attack.

To address this problem, active shooter response training programs should employ multiple means of instruction whenever possible and reinforcing learning points through direct physical or mental participation by students. Active shooter drill exercises are best for this purpose. However, conducting drills properly and safely requires properly trained instructors (lead instructor, observer-controllers, and a role player) and entails a degree of planning and logistics that often exceeds many organizations’ tolerance for inconvenience.

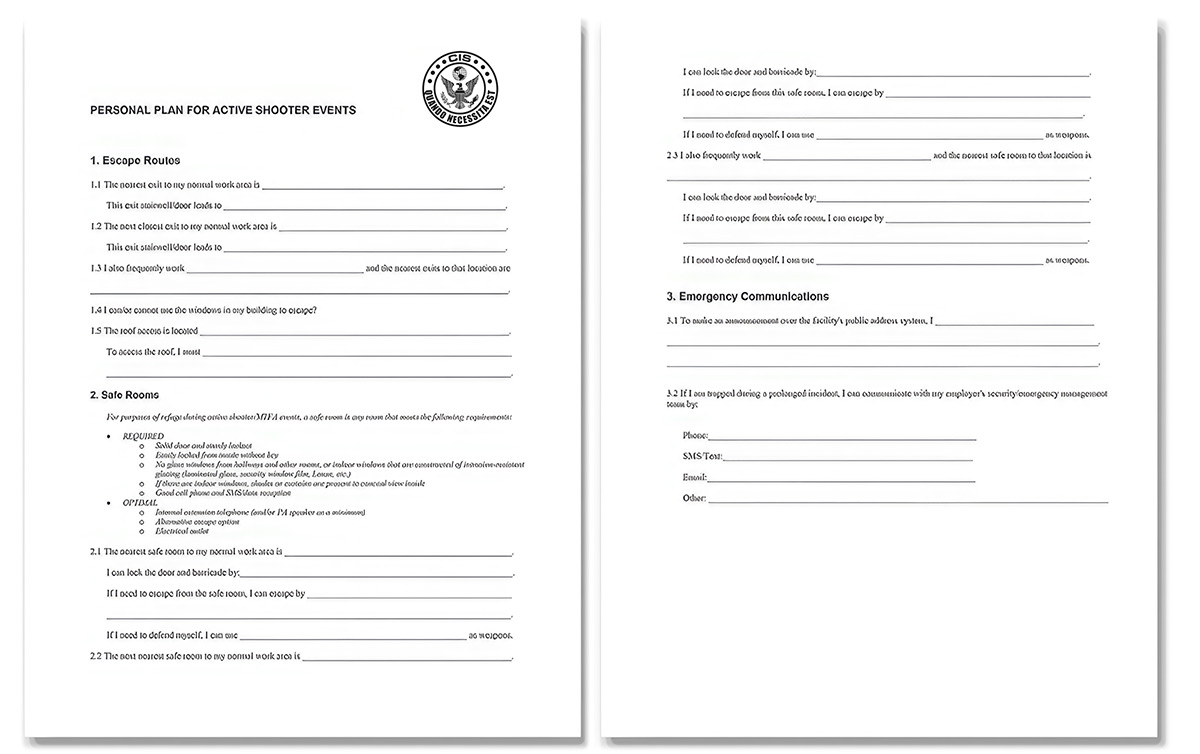

If conducting active shooter response training drills is not possible, we recommend at least addressing participants during classroom training in a manner that engages them mentally in evaluating their response options and considering how they personally might respond in their workplace situation. For this purpose, we use a classroom handout sheet titled “Personal Plan for Active Shooter Response.” The sheet has several questions organized by section to correspond with topics during the training presentation.

At designated cue points during the lecture, the presentation is paused and students are instructed to complete specific sections of the Personal Plan sheet. The purpose of the Personal Plan sheet is to provide employees with an opportunity to consider possible response situations as related to their personal work activity and reinforce long-term memory through the act of writing.

Some examples of questions include:

The nearest exit to my normal work area is ____.

I can/or cannot use the windows in my building to escape? _____. If yes, I can open the window by ____.

The nearest safe room to my normal work area is ______.

I can lock the door and barricade by: ______.

By working through a challenge mentally and reinforcing that activity through the act of writing, memory is reinforced. And if a situation does arise in the future, it is not the first time the employee has considered that challenge and there is at least a frame of reference in memory to guide action.

Be attentive to the pre-existing beliefs and psychological sensitivities of employees when designing and conducting active shooter response training

Expect that within every employee group, there will be diverse perspectives regarding the risk of active shooter violence. Some may believe it could never happen. Others may have amplified fears. Likewise, some actions that may be warranted during active shooter attacks (particularly the issue of personal defense, or what DHS traditionally calls “Fight”), naturally provoke anxiety in many people. During my experience training larger employee groups, I often encounter participants with heightened sensitivity to these issues due to a previous traumatic experience.

Unfortunately, the sensitivity of this situation is often dismissed (or at least underappreciated) by many colleagues in the tactical community who believe in “stress inoculation” by displaying graphic footage of previous shooting events and conducting high-intensity simulation exercises. Although these types of training methods are appropriate for preparing soldiers and police for combat, they often have a reverse effect on employee groups resulting in increased fear and anxiety.

Regarding the issue of diverse beliefs about risk and pre-existing fears, I recommend beginning active shooter response training sessions by verbally acknowledging these different perspectives. Our aim in this short discussion is to catch the attention of those who think it isn’t possible while also tempering any exaggerated fears. To first address the matter of amplified fears, I begin with a slide citing OSHA and CDC statistics regarding workplace fatalities underscoring the low probability of a shooting event.

Then, after acknowledging that although the likelihood of an attack is very low, emphasize that these are real events nevertheless and with potentially catastrophic consequences. To reinforce this point in classes we teach, I use a slide of FSU’s Strozer Library and tell a personal story about my daughter, Heather, who was in the Strozer Library the night of the 2014 shooting. If you as an instructor have a similar story to share, this is a great opportunity to use it.

Afterward, close the discussion by summarizing that active shooter violence is a very low probability risk, but with potentially very high consequences. And our aim as an organization is to reduce that risk responsibly by ensuring that all employees understand their role in preventing and responding to attacks.

Regarding the matter of anxiety and cracking the ‘mental permission barrier’ about self-defense, there is another approach I’ve found rather successful.

When advancing to discussion about DEFEND (DHS “Fight”), pause for a moment, scan the audience, and acknowledge the uncomfortable nature of this subject. Then ask participants to raise their hand if they have children and keep them raised. Next ask, “If you knew that the life of your child was in imminent jeopardy, could you use force (including even lethal force) to protect your child? If the answer is no, lower your hand.“

Most hands will remain raised. Even those who passionately abhor violence or feel most intimidated by this subject will usually keep their hand up. Protecting our children is one of our most primal impulses as humans.

Then ask, “And then why would you not also do so for the protection of your own life?”

Give them a quiet moment to digest that point. As you now look around the room, watch the eyes of the audience. You can often witness the ‘lightbulbs illuminating above people’s heads’ as they never thought about the matter like that before.

Recent Comments